The decade of design: How the last 10 years transformed design’s role in tech

The tech industry, which long exalted the engineer, has finally begun to appreciate the designer too.

The 2010s are coming to a close, and as different blogs recap all the highlights, we’re reminded of just how much changed in such a short period. As little as a decade ago, we didn’t live our lives glued to a smartphone. In 2010, Uber and Instagram were just getting started.

As mobile upended the way products were built, designers were called to action. Their expertise made them particularly well-suited to the challenge of distilling complex technical systems to essential interactions. Companies that had previously ran on as little design resources as possible began hiring in spades. (In one memorable run, the IBMs of the world acquired over 35 design agencies Like Groundhog Day for designers, you know spring’s a comin’ when all-star designer John Maeda drops his state of the union

The 6 design trends John Maeda predicted in his state of the union

Silicon Valley, which had long exalted the engineer, finally began to appreciate the power of the designer too. We didn’t want to let this decade pass without acknowledging the milestones and moments that made this happen. It turns out that a lot can unfold in 10 years, so to help us parse out the most important stuff, we spoke with 12 people across the industry, from design leaders to educators to investors. (To narrow scope, we focused on the U.S. but it’s worth noting these trends played out across the world.)

The mobile wave

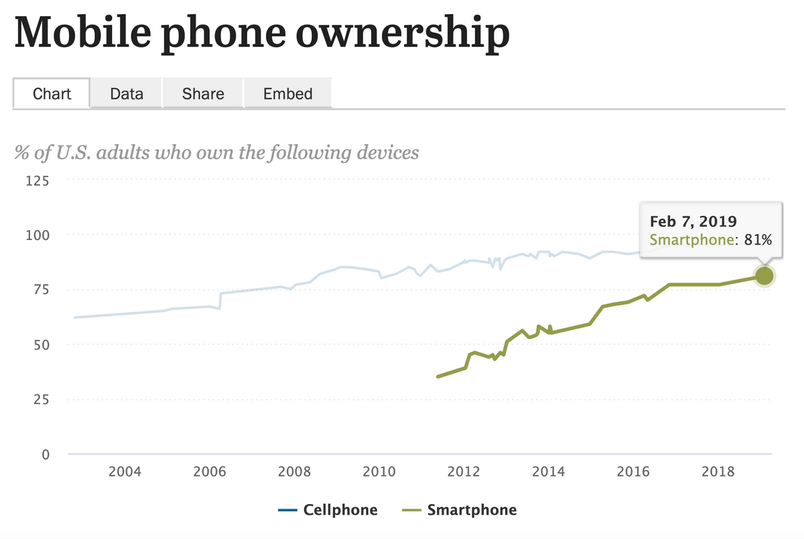

The tipping point that transformed design’s role in tech was—what else?—the iPhone. Although Apple technically introduced it last decade (2007), it didn’t enable in-app purchases until 2009 or launch the iPad until 2010. So its biggest effects were felt in the last 10 years, as mobile spread throughout the world, reshaping consumer preferences and the design that powers them.

People we spoke with named many different ways the iPhone (and resulting smartphone trend) changed UX/UI design. Here’s a few common themes.

Everything got a little more complicated

Mobile made everything more complicated. The screens were smaller than on desktop, and more varied in terms of size. They weren’t just clicking buttons with a mouse — they were using their fingers to swipe, tap, and hold, often while in motion. They might be walking, driving, standing in line at the airport, gondoliering, you get the idea.

“Mobile normalized the idea of computing beyond the screen,” said Josh Clark, the creator of the popular running app Couch to 5K and founder of the design studio Big Medium. “Our phones became the main event, the computers we use most throughout the day.”

All these factors meant companies had to make tough decisions about what functionality to prioritize—a task designers were uniquely suited for.

Data, data, data

At the same time, mobile phones brought an avalanche of new information about users. Huge swaths of the population had pocket-sized computers that could see, hear, and interact with what was nearby. People used their phones constantly, resulting in what technologist Jem Gold called “infinitely more data than anything we’d seen in 2.5 decades of software development.”

Product teams started running constant A/B tests on UI variations. They’d experiment with button color or text, seeing how it impacted sign ups, purchases, shares, or other behavior. Companies—with Facebook leading the charge—started hiring more designers to power these experiments, and data-driven design became its own discipline.

“They’re constantly nudging stuff for growth, and I don’t remember that being a job 20 years ago,” said May-Li Khoe, former VP of Design at Khan Academy. “Smartphone adoption and data usage have totally changed what design even means in the last 10 years.” She's had a front row seat for this, having worked in tech for decades, with long stints at Microsoft and Apple.

The Apple design effect

The last big impact the iPhone had on UI/UX design is an obvious one: It set the gold standard. “Applications used to be gray, bland, functional affairs imposed upon us to do the mundane tasks of the day,” Josh Clark said. “Mobile really blew that up.”

Of course, Apple had always invested in design more than most tech companies, but in the late nineties and 2000’s people balked at the price of Macs compared to PCs. So Macs stayed fringe, mostly found in hipster creative fields like video production and graphic design.

The iPhone, with its initial $499 price tag, was a little more accessible to a certain audience. It became a visible status symbol, and changed the mainstream public’s expectations for how tech products should look and feel. “It was the first time everyone and their dog could see: This looks prettier than the other thing,” said Jem Gold.

For better or worse, companies wanted to be like Apple. Consumers wanted to use products that felt like Apple. We all had iPhone-envy, and mobile-first businesses like Tinder took their design cues from the operating system that gave rise to them. Google’s Android team famously threw out the device they’d been working on for months.

The competitive market

As mobile ate the world, it became easier to start a tech company (at least in the Bay Area). A few factors lowered the barrier to entry:

- Venture funding: Because of the 2008 recession, the Federal Reserve held the interest rate at almost 0% — the lowest in US history — for 7 years. That encouraged a flood of extra money into the tech startup marketplace from traditionally risk adverse Limited Partners, like university endowments.

- AWS: Amazon re-introduced AWS in 2006, so companies could spin up instances of cloud-powered services without having to run their own server farms. By 2010 many companies were adopting this approach.

- GitHub & open source: GitHub was founded in 2008 and rose to prominence in the last decade, popularizing open source programming initiatives. Instead of having to start from scratch, companies could adapt open source code to the needs of their own product.

GitHub investor Peter Levine led Andreessen Horowitz’s $100 million Series A in the company. He sees a lot of parallels between programming’s expansion in previous decade and what’s happening in design today.

“Design represents a fundamental shift in competitive advantage,” he said. “Ten-plus years ago it was all about the code. Now it will be about the elegance of design as a first principle of software development.”

In decades past, many companies could rely on the fact that they’d secured capital and built a reliable product as a moat. They might face one or two other big competitors who’d done the same, but otherwise they’d gotten past the hardest part: Coming into existence. In the last decade that shifted and software ate the world. (Side note: That famous Marc Andreessen prediction is only 8 years old.)

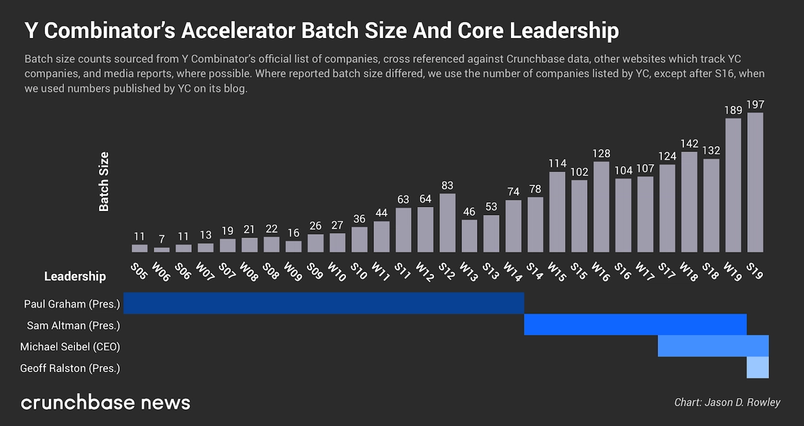

According to Crunchbase News’ analysis, the batch size of popular accelerator program Y Combinator jumped from 27 to almost 200 in the last decade. MIT economists found that in 2014, the rate of high growth startup creation hit its second highest peak in 15 US states, especially California.

Everyone began duking it out, wielding design as their weapon. “You take any duopoly you can think of. Lyft and Uber. They’re all running on AWS, the exact same thing,” said Jared Erondu, head of design at the people management platform Lattice. “So the differentiation comes from the experience of the customers and the drivers.”

To study the design tactics companies were employing, Jared and his co-creator Bobby Ghoshal interviewed 25 masters of UI design in the High Resolution video series. It’s worth a watch if you haven’t seen it before.

The rise of design (and therefore the designer)

So to recap, in 2010 a few factors converged that motivated tech companies to invest more in design. To handle the transition to mobile, they needed people trained in the power of distilling complexity to its fundamental elements. Naturally, once users got accustomed to beautiful and easy-to-use experiences on mobile, that raised their standard for all user interfaces. At the same time, it got easier to start and build a tech company than ever before, so companies faced far more competitors and had to differentiate via their user experience.

The first step for a startup looking to invest in design? Naturally, hire more designers! In doing market research for academic planning, UC Berkeley found that demand for employees trained in emerging technology and design has grown by 250% in the past 10 years.

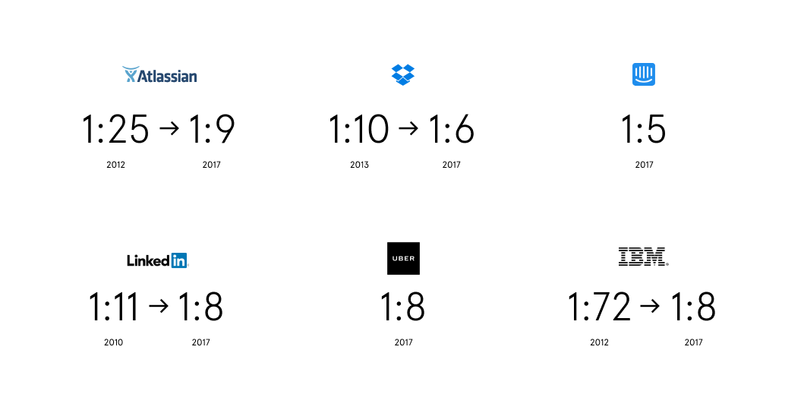

We surveyed a handful of enterprise companies in 2017, who told us they had dramatically increased their design hiring. (We’re planning to update the stats in 2020 for both consumer and enterprise companies. If you want to share yours, reach out to me.)

This was a big change from when Elizabeth Lin, the UX design manager for Lambda School, was in school. She remembers struggling to find design internships in 2012. "Nowadays, almost every company hires at least one design intern," she said.

As demand for trained designers increased, hiring became more difficult. Soleio Cuervo experienced this first hand as an early design lead at Facebook and Dropbox. Now he tries to help solve the issue for other people through Combine, the venture capital firm he co-founded.

“Design recruiting has consistently been cited as the most desirable and valuable service we can provide portfolio companies,” Soleio explained.

The ripple effect in education

At the start of the decade, traditional universities and even design schools hadn’t cottoned onto the demand. At Berkeley, one of the few tech design classes (CS160 — Introduction to Human Computer Interaction Academia hasn’t kept up with the head-spinning rise of digital design.How Figma Transformed This Berkeley Design Class

The student-taught elective on Photoshop and Illustrator fared even worse. It could fit 30 people, and once had 300 show up for it. “I believe it was harder to get accepted into it than it was to get into Berkeley,” remembered Shana Hu, one of the chosen students.

To help expand its design curriculum, Berkeley took several steps:

- Built the Jacobs Institute: In 2014, Berkeley opened the doors of the Jacobs Institute for Design Innovation. Part of the engineering school, Jacobs now offers a wide range of design classes in interdisciplinary fields like robotics and mobility.

- Introduced a new design degree: In 2019 Berkeley went even farther by introducing a new master’s program in design, with a focus on emerging technologies.

“It was very exciting to see that,” Shana said. She made the most of the options available and landed a job at Pinterest as a designer when she graduated.

Berkeley's moves, although welcomed by students and employers alike, raise an age old debate: Should the job market really dictate education curriculum? May-Li Khoe urged schools developing design programs to take a thoughtful approach (especially in regards to ethics), and not just teach it as an empty skill.

“Both coding and design have many aspects beyond vocational training,” she said. “They can shape how you think, how you see the world, how you create, how you express, how you problem solve.”

Alternative routes

Not every campus adapted as quickly as Berkeley. To bridge the gap, several bootcamps emerged in the last decade, from General Assembly (2011) to Lambda School (2017).

Online courses also got more sophisticated. In 2014, design leader Meng To released a self-published book called Design + Code, which rose to prominence quickly. He eventually hired a team and developed it into a full-blown educational website.

“I think students are starting to realize that in order to be successful, they need to use the latest tools and techniques,” said Meng. “Traditional schools simply don’t work if you are in tech.”

Many UX/UI designers found their way into the career through these kinds of sideways avenues. Front-end programmers read classic design theory books and studied basic usability principles. Graphic designers taught themselves to code. Classically trained graduates from design colleges created websites for local businesses.

It’s no wonder then that as design matures in the industry, it’s splintering into many specializations, from research, to design systems, to UX writing, to growth. Michelle Morrison, a senior design program manager at Dropbox, pointed out that in the past, one or two people might have done all of these jobs at a company. “Now we have full-stack design teams that can go deep on these problems,” she said.

The next generation of design tooling

As design evolved, so did design tooling. As a long-time Figmate, I have obvious bias on the subject, so...you know. Disclaimer ;).

Before 2010, most people who needed to design apps and interfaces were using Photoshop -- which literally has the word ‘photo’ in its name. That posed challenges, because digital design is a lot different than print. For example, print graphics appear on physical objects of a fixed size, but digital graphics are represented on screens of many different sizes (especially once mobile hit). For awhile, designers leaned on an Adobe screen design tool called Fireworks, but they discontinued it.

A dizzying array of options

So everyone welcomed the launch of UI design tool Sketch, bootstrapped out of Europe in 2010. The time was right, and Sketch kick—started a wave of design tool innovation across many different sectors, not just UI.

Many tools emerged to focus on specific parts of the toolchain that were underserved by Sketch, like prototyping (Framer and InVision) or version control (Abstract) or developer handoff (Zeplin). Some applications focused on a particular type of design, like websites (Webflow) or new audiences like non-designers (Canva). Adobe introduced XD—its answer to the broader UI design need.

As Meng To put it: “It’s both amazing and overwhelming to designers. We’re faced with so many choices.”

Design in the browser

As for Figma? We took an unconventional approach by building our professional UI design tool on the web. It had never been done before, in part because browser technology had been limited in its graphic processing abilities. But in 2011, the advent of a Javascript API called WebGL made it possible.

It’s fair to say that at first people thought we were crazy for putting a design tool in the browser (just check out the comments on DesignerNews from our 2016 launch out of beta). John Lilly, the investor at Greylock who led our Series A in 2015, took a chance on us anyway. His decision was motivated by the fact that a browser-based tool could open up the design process to everyone, like Google Docs for visual collaboration.

That’s the direction we went in, and after we honed our tool for designers, we launched a code panel for developer handoff and prototyping mode for user testing and presentations. Because files could be shared by a URL, and there were no exporting-syncing challenges, a Figma file became a source of truth that designers, engineers, product managers, copy-writers, and others could work together in.

As John put it: “Designing products, like everything else we do, is a team sport, but it was held back by the tooling.”

The design arms race

Tools have the power to change the way we think and what we can accomplish (as Wilson Miner explored in his excellent 2011 talk). And every design tool launched in the last decade has expanded the opportunities and possibilities for interface design.

In the last few years, venture capital investors cottoned onto the opportunity. Just in the professional UI design tool industry, 7 startups have raised over half a billion in venture from 20+ firms, and much of that happened in the last year alone. Five of the top venture capital firms have placed their bets.

I asked John — who was relatively early to the space in 2015 — why he thinks design is the new VC passion. “I always think of Willie Sutton’s response to the question of why he robbed banks,” John said. “‘Because that’s where the money is.’”

What comes next?

Wow, what a journey. It’s hard to believe how much has happened in 10 years alone — mobile sped up the pace of everything, design included.

Now that design has secured its seat at the table, it’s time to use that power for good. In the past 10 years, a lot of concerns have been raised about technology’s impact, from digital addiction to the spread of fake news. Many people we interviewed mentioned the moral responsibilities that lie ahead.

“Designers need to look to communities (typically underserved communities) that have long considered the ethics of designed objects, tangible and intangible,” said Amélie Lamont, who runs a product design studio out of Brooklyn. She cautioned the industry against thinking of design ethics as a “new” idea.

The topic felt like it deserved its own story, instead of being shoe-horned into an already lengthy exploration of the past decade, so stay tuned for that follow-on. In the meanwhile, we’ll let Jem close out this story with some final thoughts:

“The next 10 years are going to be critically important for the long term survival of the planet and of human civilization. We’ve seen what technology can do in a decade, so let’s make the next one count.”